Neoliberalism

| Part of the politics series on |

| Neoliberalism |

|---|

| Part of a series on |

| Capitalism |

|---|

| Part of a series on |

| Economic systems |

|---|

|

Major types

|

Neoliberalism[1] is both a political philosophy and a term used to signify the late-20th-century political reappearance of 19th-century ideas associated with free-market capitalism.[2][3][4] The term has multiple, competing definitions, and is often used pejoratively.[5][6] In scholarly use, the term is often left undefined or used to describe a multitude of phenomena;[7][8][9] however, it is primarily employed to delineate the societal transformation resulting from market-based reforms.[10]

Neoliberalism is an economic philosophy that originated among European liberal scholars during the 1930s. It emerged as a response to the perceived decline in popularity of classical liberalism, which was seen as giving way to a social liberal desire to control markets. This shift in thinking was shaped by the Great Depression and manifested in policies designed to counter the volatility of free markets.[11] One motivation for the development of policies designed to mitigate the volatility of capitalist free markets was a desire to avoid repeating the economic failures of the early 1930s, which have been attributed, in part, to the economic policy of classical liberalism. In the context of policymaking, neoliberalism is often used to describe a paradigm shift that followed the failure of the post-war consensus and neo-Keynesian economics to address the stagflation of the 1970s.[12][1] The collapse of the USSR and the end of the Cold War also facilitated the rise of neoliberalism in the United States and around the world.[13][14][15]

Neoliberalism has become increasingly prevalent term in recent decades.[16][17][18][19] It has been a significant factor in the proliferation of conservative and right-libertarian organizations, political parties, and think tanks, and predominantly advocated by them.[20][21] Neoliberalism is often associated with a set of economic liberalization policies, including privatization, deregulation, depoliticisation, consumer choice, globalization, free trade, monetarism, austerity, and reductions in government spending. These policies are designed to increase the role of the private sector in the economy and society.[22][23][24][25] Additionally, the neoliberal project is oriented towards the establishment of institutions and is inherently political in nature, extending beyond mere economic considerations.[26]

The term is rarely used by proponents of free-market policies.[27] When the term entered into common academic use during the 1980s in association with Augusto Pinochet's economic reforms in Chile, it quickly acquired negative connotations and was employed principally by critics of market reform and laissez-faire capitalism. Scholars tended to associate it with the theories of economists working with the Mont Pelerin Society, including Friedrich Hayek, Milton Friedman, Ludwig von Mises, and James M. Buchanan, along with politicians and policy-makers such as Margaret Thatcher, Ronald Reagan, and Alan Greenspan.[7][28][29] Once the new meaning of neoliberalism became established as common usage among Spanish-speaking scholars, it diffused into the English-language study of political economy.[7] By 1994, the term entered global circulation and scholarship about it has grown over the last few decades.[17][18]

Terminology

[edit]Origins

[edit]An early use of the term in English was in 1898 by the French economist Charles Gide to describe the economic beliefs of the Italian economist Maffeo Pantaleoni,[30] with the term néo-libéralisme previously existing in French;[31] the term was later used by others, including the classical liberal economist Milton Friedman in his 1951 essay "Neo-Liberalism and its Prospects".[32] In 1938, at the Colloque Walter Lippmann, neoliberalism was proposed, among other terms, and ultimately chosen to be used to describe a certain set of economic beliefs.[33][34] The colloquium defined the concept of neoliberalism as involving "the priority of the price mechanism, free enterprise, the system of competition, and a strong and impartial state".[35] According to attendees Louis Rougier and Friedrich Hayek, the competition of neoliberalism would establish an elite structure of successful individuals that would assume power in society, with these elites replacing the existing representative democracy acting on the behalf of the majority.[36][37] To be neoliberal meant advocating a modern economic policy with state intervention.[38] Neoliberal state interventionism brought a clash with the opposing laissez-faire camp of classical liberals, like Ludwig von Mises.[39] Most scholars in the 1950s and 1960s understood neoliberalism as referring to the social market economy and its principal economic theorists such as Walter Eucken, Wilhelm Röpke, Alexander Rüstow, and Alfred Müller-Armack. Although Hayek had intellectual ties to the German neoliberals, his name was only occasionally mentioned in conjunction with neoliberalism during this period due to his more pro-free market stance.[7]

During the military rule under Augusto Pinochet (1973–1990) in Chile, opposition scholars took up the expression to describe the economic reforms implemented there and its proponents (the Chicago Boys).[7] Once this new meaning was established among Spanish-speaking scholars, it diffused into the English-language study of political economy.[7] According to one study of 148 scholarly articles, neoliberalism is almost never defined but used in several senses to describe ideology, economic theory, development theory, or economic reform policy. It has become used largely as a term of abuse and/or to imply a laissez-faire market fundamentalism virtually identical to that of classical liberalism – rather than the ideas of those who attended the 1938 colloquium. As a result, there is controversy as to the precise meaning of the term and its usefulness as a descriptor in the social sciences, especially as the number of different kinds of market economies have proliferated in recent years.[7]

Unrelated to the economic philosophy, neoliberalism is used to describe a centrist political movement from modern American liberalism in the 1970s. According to political commentator David Brooks, prominent neoliberal politicians included Al Gore and Bill Clinton of the Democratic Party.[40] The neoliberals coalesced around two magazines, The New Republic and the Washington Monthly,[41] and often supported Third Way policies. The "godfather" of this version of neoliberalism was the journalist Charles Peters,[42] who in 1983 published "A Neoliberal's Manifesto".[43]

Current usage

[edit]Historian Elizabeth Shermer argued that the term gained popularity largely among left-leaning academics in the 1970s to "describe and decry a late twentieth-century effort by policymakers, think-tank experts, and industrialists to condemn social-democratic reforms and unapologetically implement free-market policies";[44] economic historian Phillip W. Magness notes its reemergence in academic literature in the mid-1980s, after French philosopher Michel Foucault brought attention to it.[45]

At a base level we can say that when we make reference to 'neoliberalism', we are generally referring to the new political, economic and social arrangements within society that emphasize market relations, re-tasking the role of the state, and individual responsibility. Most scholars tend to agree that neoliberalism is broadly defined as the extension of competitive markets into all areas of life, including the economy, politics and society.

Neoliberalism is contemporarily used to refer to market-oriented reform policies such as "eliminating price controls, deregulating capital markets, lowering trade barriers" and reducing, especially through privatization and austerity, state influence in the economy.[7] It is also commonly associated with the economic policies introduced by Margaret Thatcher in the United Kingdom and Ronald Reagan in the United States.[24] Some scholars note it has a number of distinct usages in different spheres:[46]

- As a development model, it refers to the rejection of structuralist economics in favor of the Washington Consensus.

- As an ideology, it denotes a conception of freedom as an overarching social value associated with reducing state functions to those of a minimal state.

- As a public policy, it involves the privatization of public economic sectors or services, the deregulation of private corporations, sharp decrease of government budget deficits and reduction of spending on public works.

There is debate over the meaning of the term. Sociologists Fred L. Block and Margaret Somers claim there is a dispute over what to call the influence of free-market ideas which have been used to justify the retrenchment of New Deal programs and policies since the 1980s: neoliberalism, laissez-faire or "free market ideology".[47] Other academics such as Susan Braedley, Med Luxton, and Robert W. McChesney, assert that neoliberalism is a political philosophy which seeks to "liberate" the processes of capital accumulation.[48] In contrast, Frances Fox Piven sees neoliberalism as essentially hyper-capitalism.[49] Robert W. McChesney, while defining neoliberalism similarly as "capitalism with the gloves off", goes on to assert that the term was largely unknown by the general public in 1998, particularly in the United States.[50] Lester Spence uses the term to critique trends in Black politics, defining neoliberalism as "the general idea that society works best when the people and the institutions within it work or are shaped to work according to market principles".[51] According to Philip Mirowski, neoliberalism views the market as the greatest information processor, superior to any human being. It is hence considered as the arbiter of truth. Adam Kotsko describes neoliberalism as political theology, as it goes beyond simply being a formula for an economic policy agenda and instead infuses it with a moral ethos that "aspires to be a complete way of life and a holistic worldview, in a way that previous models of capitalism did not."[52]

Neoliberalism is distinct from liberalism insofar as it does not advocate laissez-faire economic policy, but instead is highly constructivist and advocates a strong state to bring about market-like reforms in every aspect of society.[53] Anthropologist Jason Hickel also rejects the notion that neoliberalism necessitates the retreat of the state in favor of totally free markets, arguing that the spread of neoliberalism required substantial state intervention to establish a global 'free market'.[54] Naomi Klein states that the three policy pillars of neoliberalism are "privatization of the public sphere, deregulation of the corporate sector, and the lowering of income and corporate taxes, paid for with cuts to public spending".[55]

According to some scholars, neoliberalism is commonly used as a pejorative by critics, outpacing similar terms such as monetarism, neoconservatism, the Washington Consensus and "market reform" in much scholarly writing.[7] The Handbook of Neoliberalism, for instance, posits that the term has "become a means of identifying a seemingly ubiquitous set of market-oriented policies as being largely responsible for a wide range of social, political, ecological and economic problems".[10] Its use in this manner has been criticized by those who advocate for policies characterized as neoliberal.[56] The Handbook, for example, further argues that "such lack of specificity [for the term] reduces its capacity as an analytic frame. If neoliberalism is to serve as a way of understanding the transformation of society over the last few decades, then the concept is in need of unpacking."[10] Historian Daniel Stedman Jones has similarly said that the term "is too often used as a catch-all shorthand for the horrors associated with globalization and recurring financial crises".[57]

Several writers have criticized neoliberal as an insult or slur used by leftists against liberals and varieties of liberalism that leftists disagree with.[58][59] British journalist Will Hutton called neoliberal "an unthinking leftist insult" that "stifle[s] debate."[60] On the other hand, many scholars believe it retains a meaningful definition. Writing in The Guardian, Stephen Metcalf posits that the publication of the 2016 IMF paper "Neoliberalism: Oversold?"[61] helps "put to rest the idea that the word is nothing more than a political slur, or a term without any analytic power".[62] Gary Gerstle argues that neoliberalism is a legitimate term,[63] and describes it as "a creed that calls explicitly for unleashing capitalism's power."[64] He distinguishes neoliberalism from traditional conservatism, as the latter values respect for traditions and bolstering the institutions which reinforce them, whereas the former seeks to disrupt and overcome any institutions which stand in the way.[64]

Radhika Desai, director of the Geopolitical Economy Research Group at the University of Manitoba, argues that global capitalism reached its peak in 1914, just prior to the two great wars, anti-capitalist revolutions and Keynesian reforms, and the purpose of neoliberalism was to restore capitalism to the preeminence it once enjoyed. She argues that this process has failed as contemporary neoliberal capitalism has fostered a "slowly unfolding economic disaster" and bequeathed to the world increased inequalities, societal divisions, economic misery and a lack of meaningful politics.[65]

Early history

[edit]Walter Lippmann Colloquium

[edit]

The Great Depression in the 1930s, which severely decreased economic output throughout the world and produced high unemployment and widespread poverty, was widely regarded as a failure of economic liberalism.[67] To renew the damaged ideology, a group of 25 liberal intellectuals, including a number of prominent academics and journalists like Walter Lippmann, Friedrich Hayek, Ludwig von Mises, Wilhelm Röpke, Alexander Rüstow, and Louis Rougier, organized the Walter Lippmann Colloquium, named in honor of Lippmann to celebrate the publication of the French translation of Lippmann's pro-market book An Inquiry into the Principles of the Good Society.[68][69] Meeting in Paris in August 1938, they called for a new liberal project, with "neoliberalism" one name floated for the fledgling movement.[70] They further agreed to develop the Colloquium into a permanent think tank based in Paris called the Centre International d'Études pour la Rénovation du Libéralisme.[71]

While most agreed that the status quo liberalism promoting laissez-faire economics had failed, deep disagreements arose around the proper role of the state. A group of "true (third way) neoliberals" centered around Rüstow and Lippmann advocated for strong state supervision of the economy while a group of old school liberals centered around Mises and Hayek continued to insist that the only legitimate role for the state was to abolish barriers to market entry. Rüstow wrote that Hayek and Mises were relics of the liberalism that caused the Great Depression while Mises denounced the other faction, complaining that the ordoliberalism they advocated really meant "ordo-interventionism".[72]

Divided in opinion and short on funding, the Colloquium was mostly ineffectual; related attempts to further neoliberal ideas, such as the effort by Colloque-attendee Wilhelm Röpke to establish a journal of neoliberal ideas, mostly floundered.[68] Fatefully, the efforts of the Colloquium would be overwhelmed by the outbreak of World War II and were largely forgotten.[73] Nonetheless, the Colloquium served as the first meeting of the nascent neoliberal movement and would serve as the precursor to the Mont Pelerin Society, a far more successful effort created after the war by many of those who had been present at the Colloquium.[74]

Mont Pelerin Society

[edit]

Neoliberalism began accelerating in importance with the establishment of the Mont Pelerin Society in 1947, whose founding members included Friedrich Hayek, Milton Friedman, Karl Popper, George Stigler and Ludwig von Mises. Meeting annually, it became a "kind of international 'who's who' of the classical liberal and neo-liberal intellectuals."[75][76] While the first conference in 1947 was almost half American, the Europeans dominated by 1951. Europe would remain the epicenter of the community as Europeans dominated the leadership roles.[77]

Established during a time when central planning was in the ascendancy worldwide and there were few avenues for neoliberals to influence policymakers, the society became a "rallying point" for neoliberals, as Milton Friedman phrased it, bringing together isolated advocates of liberalism and capitalism. They were united in their belief that individual freedom in the developed world was under threat from collectivist trends,[74] which they outlined in their statement of aims:

The central values of civilization are in danger. Over large stretches of the Earth's surface the essential conditions of human dignity and freedom have already disappeared. In others, they are under constant menace from the development of current tendencies of policy. The position of the individual and the voluntary group are progressively undermined by extensions of arbitrary power. Even that most precious possession of Western Man, freedom of thought and expression, is threatened by the spread of creeds which, claiming the privilege of tolerance when in the position of a minority, seek only to establish a position of power in which they can suppress and obliterate all views but their own...The group holds that these developments have been fostered by the growth of a view of history which denies all absolute moral standards and by the growth of theories which question the desirability of the rule of law. It holds further that they have been fostered by a decline of belief in private property and the competitive market...[This group's] object is solely, by facilitating the exchange of views among minds inspired by certain ideals and broad conceptions held in common, to contribute to the preservation and improvement of the free society.[78]

The society set out to develop a neoliberal alternative to, on the one hand, the laissez-faire economic consensus that had collapsed with the Great Depression and, on the other, New Deal liberalism and British social democracy, collectivist trends which they believed posed a threat to individual freedom.[74] They believed that classical liberalism had failed because of crippling conceptual flaws which could only be diagnosed and rectified by withdrawing into an intensive discussion group of similarly minded intellectuals;[79] however, they were determined that the liberal focus on individualism and economic freedom must not be abandoned to collectivism.[80]

Post–World War II neoliberal currents

[edit]For decades after the formation of the Mont Pelerin Society, the ideas of the society would remain largely on the fringes of political policy, confined to a number of think-tanks and universities[81] and achieving only measured success with the ordoliberals in Germany, who maintained the need for strong state influence in the economy. It would not be until a succession of economic downturns and crises in the 1970s that neoliberal policy proposals would be widely implemented. By this time, neoliberal thought had evolved. The early neoliberal ideas of the Mont Pelerin Society had sought to chart a middle way between the trend of increasing government intervention implemented after the Great Depression and the laissez-faire economics many in the society believed had produced the Great Depression. Milton Friedman, wrote in his early essay "Neo-liberalism and Its Prospects" that "Neo-liberalism would accept the nineteenth-century liberal emphasis on the fundamental importance of the individual, but it would substitute for the nineteenth century goal of laissez-faire as a means to this end, the goal of the competitive order", which requires limited state intervention to "police the system, establish conditions favorable to competition and prevent monopoly, provide a stable monetary framework, and relieve acute misery and distress."[82] By the 1970s, neoliberal thought—including Friedman's—focused almost exclusively on market liberalization and was adamant in its opposition to nearly all forms of state interference in the economy.[74]

One of the earliest and most influential turns to neoliberal reform occurred in Chile after an economic crisis in the early 1970s. After several years of socialist economic policies under president Salvador Allende, a 1973 coup d'état, which established a military junta under dictator Augusto Pinochet, led to the implementation of a number of sweeping neoliberal economic reforms that had been proposed by the Chicago Boys, a group of Chilean economists educated under Milton Friedman. This "neoliberal project" served as "the first experiment with neoliberal state formation" and provided an example for neoliberal reforms elsewhere.[83] Beginning in the early 1980s, the Reagan administration and Thatcher government implemented a series of neoliberal economic reforms to counter the chronic stagflation the United States and United Kingdom had each experienced throughout the 1970s. Neoliberal policies continued to dominate American and British politics until the Great Recession.[74] Following British and American reform, neoliberal policies were exported abroad, with countries in Latin America, the Asia-Pacific, the Middle East, and China implementing significant neoliberal reform. Additionally, the International Monetary Fund and World Bank encouraged neoliberal reforms in many developing countries by placing reform requirements on loans, in a process known as structural adjustment.[84]

Germany

[edit]

Neoliberal ideas were first implemented in West Germany. The economists around Ludwig Erhard drew on the theories they had developed in the 1930s and 1940s and contributed to West Germany's reconstruction after the Second World War.[85] Erhard was a member of the Mont Pelerin Society and in constant contact with other neoliberals. He pointed out that he is commonly classified as neoliberal and that he accepted this classification.[86]

The ordoliberal Freiburg School was more pragmatic. The German neoliberals accepted the classical liberal notion that competition drives economic prosperity. However, they argued that a laissez-faire state policy stifles competition, as the strong devour the weak since monopolies and cartels could pose a threat to freedom of competition. They supported the creation of a well-developed legal system and capable regulatory apparatus. While still opposed to full-scale Keynesian employment policies or an extensive welfare state, German neoliberal theory was marked by the willingness to place humanistic and social values on par with economic efficiency. Alfred Müller-Armack coined the phrase "social market economy" to emphasize the egalitarian and humanistic bent of the idea.[7] According to Boas and Gans-Morse, Walter Eucken stated that "social security and social justice are the greatest concerns of our time".[7]

Erhard emphasized that the market was inherently social and did not need to be made so.[87] He hoped that growing prosperity would enable the population to manage much of their social security by self-reliance and end the necessity for a widespread welfare state. By the name of Volkskapitalismus, there were some efforts to foster private savings. Although average contributions to the public old age insurance were quite small, it remained by far the most important old age income source for a majority of the German population, therefore despite liberal rhetoric the 1950s witnessed what has been called a "reluctant expansion of the welfare state". To end widespread poverty among the elderly the pension reform of 1957 brought a significant extension of the German welfare state which already had been established under Otto von Bismarck.[88] Rüstow, who had coined the label "neoliberalism", criticized that development tendency and pressed for a more limited welfare program.[87]

Hayek did not like the expression "social market economy", but stated in 1976 that some of his friends in Germany had succeeded in implementing the sort of social order for which he was pleading while using that phrase. In Hayek's view, the social market economy's aiming for both a market economy and social justice was a muddle of inconsistent aims.[89] Despite his controversies with the German neoliberals at the Mont Pelerin Society, Ludwig von Mises stated that Erhard and Müller-Armack accomplished a great act of liberalism to restore the German economy and called this "a lesson for the US".[90] According to different research Mises believed that the ordoliberals were hardly better than socialists. As an answer to Hans Hellwig's complaints about the interventionist excesses of the Erhard ministry and the ordoliberals, Mises wrote: "I have no illusions about the true character of the politics and politicians of the social market economy". According to Mises, Erhard's teacher Franz Oppenheimer "taught more or less the New Frontier line of" President Kennedy's "Harvard consultants (Schlesinger, Galbraith, etc.)".[91]

In Germany, neoliberalism at first was synonymous with both ordoliberalism and social market economy. But over time the original term neoliberalism gradually disappeared since social market economy was a much more positive term and fit better into the Wirtschaftswunder (economic miracle) mentality of the 1950s and 1960s.[87]

Latin America

[edit]In the 1980s, numerous governments in Latin America adopted neoliberal policies.[92][93][94]

Chile

[edit]Chile was among the earliest nations to implement neoliberal reform. Marxist economic geographer David Harvey has described the substantial neoliberal reforms in Chile beginning in the 1970s as "the first experiment with neoliberal state formation", which would provide "helpful evidence to support the subsequent turn to neoliberalism in both Britain... and the United States."[95] Similarly, Vincent Bevins says that Chile under Augusto Pinochet "became the world's first test case for 'neoliberal' economics."[96]

The turn to neoliberal policies in Chile originated with the Chicago Boys, a select group of Chilean students who, beginning in 1955, were invited to the University of Chicago to pursue postgraduate studies in economics. They studied directly under Milton Friedman and his disciple, Arnold Harberger, and were exposed to Friedrich Hayek. Upon their return to Chile, their neoliberal policy proposals—which centered on widespread deregulation, privatization, reductions to government spending to counter high inflation, and other free-market policies[97]—would remain largely on the fringes of Chilean economic and political thought for a number of years, as the presidency of Salvador Allende (1970–1973) brought about a socialist reorientation of the economy.[98]

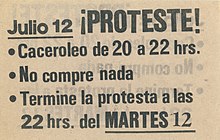

During the Allende presidency, Chile experienced a severe economic crisis, in which inflation peaked near 150%.[99] Following an extended period of social unrest and political tension, as well as diplomatic, economic, and covert pressure from the United States,[100] the Chilean armed forces and national police overthrew the Allende government in a coup d'état.[101] They established a repressive military junta, known for its violent suppression of opposition, and appointed army chief Augusto Pinochet Supreme Head of the nation.[102] His rule was later given legal legitimacy through a controversial 1980 plebiscite, which approved a new constitution drafted by a government-appointed commission that ensured Pinochet would remain as president for a further eight years—with increased powers—after which he would face a re-election referendum.[103]

The Chicago Boys were given significant political influence within the military dictatorship, and they implemented sweeping economic reform. In contrast to the extensive nationalization and centrally planned economic programs supported by Allende, the Chicago Boys implemented rapid and extensive privatization of state enterprises, deregulation, and significant reductions in trade barriers during the latter half of the 1970s.[104] In 1978, policies that would further reduce the role of the state and infuse competition and individualism into areas such as labor relations, pensions, health and education were introduced.[7]> Additionally, the central bank raised interest rates from 49.9% to 178% to counter high inflation.[105]

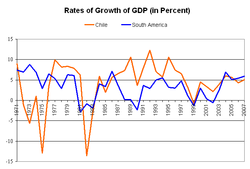

These policies amounted to a shock therapy, which rapidly transformed Chile from an economy with a protected market and strong government intervention into a liberalized, world-integrated economy, where market forces were left free to guide most of the economy's decisions.[108] Inflation was tempered, falling from over 600% in 1974, to below 50% by 1979, to below 10% right before the economic crisis of 1982;[109] GDP growth spiked (see chart) to 10%.[110] however, inequality widened as wages and benefits to the working class were reduced.[111][112]

In 1982, Chile again experienced a severe economic recession. The cause of this is contested but most scholars believe the Latin American debt crisis—which swept nearly all of Latin America into financial crisis—was a primary cause.[113] Some scholars argue the neoliberal policies of the Chicago boys heightened the crisis (for instance, percent GDP decrease was higher than in any other Latin American country) or even caused it;[113] for instance, some scholars criticize the high interest rates of the period which—while stabilizing inflation—hampered investment and contributed to widespread bankruptcy in the banking industry. Other scholars fault governmental departures from the neoliberal agenda; for instance, the government pegged the Chilean peso to the US dollar, against the wishes of the Chicago Boys, which economists believe led to an overvalued peso.[114][115]

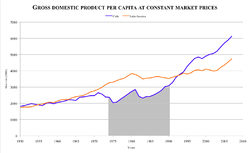

After the recession, Chilean economic growth rose quickly, eventually hovering between 5% and 10% and significantly outpacing the Latin American average (see chart). Additionally, unemployment decreased[116] and the percent of the population below the poverty line declined from 50% in 1984 to 34% by 1989.[117] This led Milton Friedman to call the period the "Miracle of Chile", and he attributed the successes to the neoliberal policies of the Chicago boys. Some scholars attribute the successes to the re-regulation of the banking industry and a number of targeted social programs designed to alleviate poverty.[117] Others say that while the economy had stabilized and was growing by the late 1980s, inequality widened: nearly 45% of the population had fallen into poverty while the wealthiest 10% had seen their incomes rise by 83%.[118] According to Chilean economist Alejandro Foxley, when Pinochet finished his 17-year term by 1990, around 44% of Chilean families were living below the poverty line.[119][120][non-primary source needed]

Despite years of suppression by the Pinochet junta, a presidential election was held in 1988, as dictated by the 1980 constitution (though not without Pinochet first holding another plebiscite in an attempt to amend the constitution).[103] In 1990, Patricio Aylwin was democratically elected, bringing an end to the military dictatorship. The reasons cited for Pinochet's acceptance of democratic transition are numerous. Hayek, echoing arguments he had made years earlier in The Road to Serfdom,[121] argued that the increased economic freedom he believed the neoliberal reforms had brought had put pressure on the dictatorship over time, resulting in a gradual increase in political freedom and, ultimately, the restoration of democracy.[citation needed] The Chilean scholars Javier Martínez and Alvaro Díaz reject this argument, pointing to the long tradition of democracy in Chile. They assert that the defeat of the Pinochet regime and the return of democracy came primarily from large-scale mass rebellion that eventually forced party elites to use existing institutional mechanisms to restore democracy.[122]

In the 1990s, neoliberal economic policies broadened and deepened, including unilateral tariff reductions and the adoption of free trade agreements with a number of Latin American countries and Canada.[123] At the same time, the decade brought increases in government expenditure on social programs to tackle poverty and poor quality housing.[124] Throughout the 1990s, Chile maintained high growth, averaging 7.3% from 1990 to 1998.[123] Eduardo Aninat, writing for the IMF journal Finance & Development, called the period from 1986 to 2000 "the longest, strongest, and most stable period of growth in [Chile's] history."[123] In 1999, there was a brief recession brought about by the Asian financial crisis, with growth resuming in 2000 and remaining near 5% until the Great Recession.[125]

In sum, the neoliberal policies of the 1980s and 1990s—initiated by a repressive authoritarian government—transformed the Chilean economy from a protected market with high barriers to trade and hefty government intervention into one of the world's most open free-market economies.[126][108] Chile experienced the worst economic bust of any Latin American country during the Latin American debt crisis (several years into neoliberal reform), but also had one of the most robust recoveries,[127] rising from the poorest Latin American country in terms of GDP per capita in 1980 (along with Peru) to the richest in 2019.[128] Average annual economic growth from the mid-1980s to the Asian crisis in 1997 was 7.2%, 3.5% between 1998 and 2005, and growth in per capita real income from 1985 to 1996 averaged 5%—all outpacing Latin American averages.[127][129] Inflation was brought under control.[109] Between 1970 and 1985 the infant mortality rate in Chile fell from 76.1 per 1000 to 22.6 per 1000,[130] the lowest in Latin America.[131] Unemployment from 1980 to 1990 decreased, but remained higher than the South American average (which was stagnant). And despite public perception among Chileans that economic inequality has increased, Chile's Gini coefficient has in fact dropped from 56.2 in 1987 to 46.6 in 2017.[128][132] While this is near the Latin American average, Chile still has one of the highest Gini coefficients in the OECD, an organization of mostly developed countries that includes Chile but not most other Latin American countries.[133] Furthermore, the Gini coefficient measures only income inequality; Chile has more mixed inequality ratings in the OECD's Better Life Index, which includes indexes for more factors than only income, like housing and education.[134][128] Additionally, the percentage of the Chilean population living in poverty rose from 17% in 1969 to 45% in 1985[135] at the same time government budgets for education, health and housing dropped by over 20% on average.[136] The era was also marked by economic instability.[137]

Overall, scholars have mixed opinions on the effects of the neoliberal reforms. The CIA World Factbook states that Chile's "sound economic policies", maintained consistently since the 1980s, "have contributed to steady economic growth in Chile and have more than halved poverty rates,"[138] and some scholars have even called the period the "Miracle of Chile". Other scholars have called it a failure that led to extreme inequalities in the distribution of income and resulted in severe socioeconomic damage.[107] It is also contested how much these changes were the result of neoliberal economic policies and how much they were the result of other factors;[137] in particular, some scholars argue that after the Crisis of 1982 the "pure" neoliberalism of the late 1970s was replaced by a focus on fostering a social market economy that mixed neoliberal and social welfare policies.[139][140]

As a response to the 2019–20 Chilean protests, a national plebiscite was held in October 2020 to decide whether the Chilean constitution would be rewritten. The "approve" option for a new constitution to replace the Pinochet-era constitution, which entrenched certain neoliberal principles into the country's basic law, won with 78% of the vote.[141][142] However, in September 2022, the referendum to approve a rewritten the constitution was rejected with 61% of the vote.

Peru

[edit]Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto, the founder of one of the first neoliberal organizations in Latin America, Institute for Liberty and Democracy (ILD), began to receive assistance from Ronald Reagan's administration, with the National Endowment for Democracy's Center for International Private Enterprise (CIPE) providing his ILD with funding.[143][144][145] The economic policy of President Alan García distanced Peru from international markets, resulting in lower foreign investment in the country.[146] Under García, Peru experienced hyperinflation and increased confrontations with the guerrilla group Shining Path, leading the country towards high levels of instability.[147] The Peruvian armed forces grew frustrated with the inability of the García administration to handle the nation's crises and began to draft an operation – Plan Verde – to overthrow his government.[147]

The military's Plan Verde involved the "total extermination" of impoverished and indigenous Peruvians perceived as a drain on the economy, the control or censorship of media in the nation and the establishment of a neoliberal economy in Peru.[148][147] During his campaigning for the 1990 Peruvian general election, Alberto Fujimori initially expressed concern against the proposed neoliberal policies of his opponent Mario Vargas Llosa.[149] Peruvian magazine Oiga reported that, following the election, the armed forces were unsure of Fujimori's willingness to fulfill the plan's objectives, though they planned to convince Fujimori to agree to the operation prior to his inauguration.[150] After taking office, Fujimori abandoned his campaign's economic platform, adopting more aggressive neoliberal policies than those espoused by his election competitor Vargas Llosa.[151] With Fujimori's compliance, plans for a coup as designed in Plan Verde were prepared for two years and finally executed during the 1992 Peruvian coup d'état, which ultimately established a civilian-military regime.[152][150]

Shortly after the inauguration of Fujimori, his government received a $715 million grant from United States Agency for International Development (USAID) on 29 September 1990 for the Policy Analysis, Planning and Implementation Project (PAPI) that was developed "to support economic policy reform in the country".[153] De Soto proved to be influential to Fujimori, who began to repeat de Soto's advocacy for deregulating the Peruvian economy.[154] Under Fujimori, de Soto served as "the President's personal representative", with The New York Times describing de Soto as an "overseas salesman", while others dubbed de Soto as the "informal president" for Fujimori.[155][143] In a recommendation to Fujimori, de Soto called for a "shock" to Peru's economy.[143] The policies included a 300% tax increase, unregulated prices and privatizing two-hundred and fifty state-owned entities.[143] The policies of de Soto led to the immediate suffering of poor Peruvians who saw unregulated prices increase rapidly.[143] Those living in poverty saw prices increase so much that they could no longer afford food.[143] The New York Times wrote that de Soto advocated for the collapse of Peru's society, with the economist saying that a civil crisis was necessary to support the policies of Fujimori.[156] Fujimori and de Soto would ultimately break their ties after de Soto recommended increased involvement of citizens within the government, which was received with disapproval by Fujimori.[157] USAID would go on to assist the Fujimori government with rewriting the 1993 Peruvian constitution, with the agency concluding in 1997 that it helped with the "preparation of legislative texts" and "contributed to the emergence of a private sector advisory role".[158][153] The policies promoted by de Soto and implemented by Fujimori eventually caused macroeconomic stability and a reduction in the rate of inflation, though Peru's poverty rate remained largely unchanged with over half of the population living in poverty in 1998.[143][159][160]

According to the Foundation for Economic Education, USAID, the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) and the Nippon Foundation also supported the sterilization efforts of the Fujimori government.[161] E. Liagin reported that from 1993 to 1998, USAID "basically took charge of the national health system of Peru" during the period of forced sterilizations.[161] At least 300,000 Peruvians were victims of forced sterilization by the Fujimori government in the 1990s, with the majority being affected by the PNSRPF.[148] The policy of sterilizations resulted in a generational shift that included a smaller younger generation that could not provide economic stimulation to rural areas, making such regions more impoverished.[162]

Though economic statistics show improved economic data in Peru in recent decades, the wealth earned between 1990 and 2020 was not distributed throughout the country; living standards showed disparities between the more-developed capital city of Lima and similar coastal regions while rural provinces remained impoverished.[163][164][165] Sociologist Maritza Paredes of the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru stated, "People see that all the natural resources are in the countryside but all the benefits are concentrated in Lima."[163] In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic in Peru compounded these disparities,[164][165] with political scientist Professor Farid Kahhat of the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru stating that, "market reforms in Peru have yielded positive results in terms of reducing poverty ... But what the pandemic has laid bare, particularly in Peru, is that poverty was reduced while leaving the miserable state of public services unaltered – most clearly in the case of health services."[164] The candidacy of Pedro Castillo in the 2021 Peruvian general election brought attention to the disparities between urban and rural Peruvians, with much of his support being earned in the exterior portions of the country.[165] Castillo ultimately won the election, with The New York Times reporting his victory as the "clearest repudiation of the country's establishment".[166][167]

Argentina

[edit]In the 1960s, Latin American intellectuals began to notice the ideas of ordoliberalism; they often used the Spanish term "neoliberalismo" to refer to this school of thought. They were particularly impressed by the social market economy and the Wirtschaftswunder ("economic miracle") in Germany and speculated about the possibility of accomplishing similar policies in their own countries. Neoliberalism in 1960s Argentina meant a philosophy that was more moderate than entirely Laissez-faire free-market capitalism and favored using state policy to temper social inequality and counter a tendency towards monopoly.[7]

In 1976, the military dictatorship's economic plan led by José Alfredo Martínez de Hoz was the first attempt at establishing a neoliberal program in Argentina. They implemented a fiscal austerity plan that reduced money printing in an attempt to counter inflation. In order to achieve this, salaries were frozen; however, they were unable to reduce inflation, which led to a drop in the real salary of the working class. They also liberalized trade policy so that foreign goods could freely enter the country. Argentina's industry, which had been on the rise for 20 years after the economic policies of former president Arturo Frondizi, rapidly declined as it was not able to compete with foreign goods. Following the measures, there was an increase in poverty from 9% in 1975 to 40% at the end of 1982.[111]

From 1989 to 2001, more neoliberal policies were implemented by Domingo Cavallo. This time, the privatization of public services was the main focus, although financial deregulation and free trade with foreign nations were also re-implemented. Along with an increased labour market flexibility, the unemployment rate dropped to 18.3%.[168] Public perception of the policies was mixed; while some of the privatization was welcomed, much of it was criticized for not being in the people's best interests. Protests resulted in the death of 29 people at the hands of police.[169]

Mexico

[edit]Along with many other Latin American countries in the early 1980s, Mexico experienced a debt crisis. In 1983 the Mexican government ruled by the PRI, the Institutional Revolutionary Party, accepted loans from the IMF. Among the conditions set by the IMF were requirements for Mexico to privatize state-run industries, devalue their currency, decrease trade barriers, and restrict governmental spending.[170] These policies were aimed at stabilizing Mexico's economy in the short run. Later, Mexico tried to expand these policies to encourage growth and foreign direct investment (FDI).

The decision to accept the IMF's neoliberal reforms split the PRI between those on the right who wanted to implement neoliberal policies and those the left who did not.[171] Carlos Salinas de Gortari, who took power in 1988, doubled down on neoliberal reforms. His policies opened up the financial sector by deregulating the banking system and privatizing commercial banks.[170][171] Though these policies did encourage a small amount of growth and FDI, the growth rate was below what it had been under previous governments in Mexico, and the increase in foreign investment was largely from existing investors.[171]

On 1 January 1994 the Zapatista Army of National Liberation, named for Emiliano Zapata, a leader in the Mexican revolution, launched an armed rebellion against the Mexican government in the Chiapas region.[172] Among their demands were rights for indigenous Mexicans as well as opposition to the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which solidified a strategic alliance between state and business.[173] NAFTA, a trade agreement between the United States, Canada, and Mexico, significantly aided in Mexico's efforts to liberalize trade.

In 1994, the same year of the Zapatista rebellion and the enactment of NAFTA, Mexico faced a financial crisis. The crisis, also known as the "Tequila Crisis" began in December 1994 with the devaluation of the peso.[171][174] When investors' doubts led to negative speculation they fled with their capital. The central bank was forced to raise interest rates which in turn collapsed the banking system as borrowers could no longer pay back their loans.[174]

After Salinas, Ernesto Zedillo (1995–2000) maintained similar economic policies to his predecessor. Despite the crisis, Zedillo continued to enact neoliberal policies and signed new agreements with the World Bank and the IMF.[171] As a result of these policies and the 1994 recession, Mexico's economy did gain stability. Neither the 2001 or 2008 recessions were caused by internal economic forces in Mexico. Trade increased dramatically, as well as FDI; however, as Mexico's business cycle synced with that of the United States, it was much more vulnerable to external economic pressures.[170] FDI benefited the Northern and Central regions of Mexico while the Southern region was largely excluded from the influx of investment. The crisis also left the banks mainly in the hands of foreigners.

The PRI's 71-year rule ended when Vicente Fox of the PAN, the National Action Party, won the election in 2000. Fox and his successor, Felipe Calderón, did not significantly diverge from the economic policies of the PRI governments. They continued to privatize the financial system and encourage foreign investment.[171] Despite significant opposition, Enrique Peña Nieto, president from 2012 to 2018, pushed through legislation that would privatize the oil and electricity industries. These reforms marked the conclusion to the neoliberal goals that had been envisioned in Mexico in the 1980s.[171]

Brazil

[edit]Brazil adopted neoliberal policies in the late 1980s, with support from the worker's party on the left. For example, tariff rates were cut from 32% in 1990 to 14% in 1994. During this period, Brazil effectively ended its policy of maintaining a closed economy focused on import substitution industrialization in favor of a more open economic system with a much higher degree of privatization. The market reforms and trade reforms ultimately resulted in price stability and a faster inflow of capital but had little effect on income inequality and poverty. Consequently, mass protests continued during the period.[175][176]

United Kingdom

[edit]During her tenure as Conservative Prime Minister from 1979 to 1990, Margaret Thatcher oversaw a number of neoliberal policies, including tax reduction, exchange rate reform, deregulation, and privatisation.[46] These policies were continued and supported by her successor John Major. Although opposed by the Labour Party, the policies were, according to some scholars, largely accepted and left unaltered when Labour returned to power in 1997 during the New Labour era under Tony Blair.[21][177]

The Adam Smith Institute, a United Kingdom–based free-market think tank and lobbying group formed in 1977 which was a major driver of the aforementioned neoliberal policies,[178] officially changed its libertarian label to neoliberal in October 2016.[179]

According to economists Denzau and Roy, the "shift from Keynesian ideas toward neoliberalism influenced the fiscal policy strategies of New Democrats and New Labour in both the White House and Whitehall.... Reagan, Thatcher, Clinton, and Blair all adopted broadly similar neoliberal beliefs."[180][181]

United States

[edit]While a number of recent histories of neoliberalism[182][183][184] in the United States have traced its origins back to the urban renewal policies of the 1950s, Marxist economic geographer David Harvey argues the rise of neoliberal policies in the United States occurred during the 1970s energy crisis,[185] and traces the origin of its political rise to Lewis Powell's 1971 confidential memorandum to the Chamber of Commerce in particular.[186] A call to arms to the business community to counter criticism of the free enterprise system, it was a significant factor in the rise of conservative and libertarian organizations and think-tanks which advocated for neoliberal policies, such as the Business Roundtable, The Heritage Foundation, the Cato Institute, Citizens for a Sound Economy, Accuracy in Academia and the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research.[187] For Powell, universities were becoming an ideological battleground, and he recommended the establishment of an intellectual infrastructure to serve as a counterweight to the increasingly popular ideas of Ralph Nader and other opponents of big business.[188][189][185] The original neoliberals included, among others, Michael Kinsley, Charles Peters, James Fallows, Nicholas Lemann, Bill Bradley, Bruce Babbitt, Gary Hart, and Paul Tsongas. Sometimes called "Atari Democrats", these were the men who helped to remake American liberalism into neoliberalism, culminating in the election of Bill Clinton in 1992. These new liberals disagreed with the policies and programs of mid-century figures like progressive labor organizer Walter Reuther, economist John Kenneth Galbraith or even noted historian Arthur Schlesinger.[190]

Early roots of neoliberalism were laid in the 1970s during the Nixon administration, with appointment of associates of Milton Friedman to Departments of Treasury, Agriculture and Justice, and the Council of Economic Advisors and encouraged funding of the American Enterprise Institute and defunding of the more centrist Brookings Institution,[191] and during the Carter administration, with deregulation of the trucking, banking and airline industries,[192][193][194] the appointment of Paul Volcker to chairman of the Federal Reserve[195] as well as increased military spending at the end of his term leading to fiscal austerity in US nonmilitary budget diverting funds away from social programs.[191] This trend continued into the 1980s under the Reagan administration, which included tax cuts, increased defense spending, financial deregulation and trade deficit expansion.[196] Likewise, concepts of supply-side economics, discussed by the Democrats in the 1970s, culminated in the 1980 Joint Economic Committee report "Plugging in the Supply Side". This was picked up and advanced by the Reagan administration, with Congress following Reagan's basic proposal and cutting federal income taxes across the board by 25% in 1981.[197]

The Clinton administration embraced neoliberalism[21] by supporting the passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), continuing the deregulation of the financial sector through passage of the Commodity Futures Modernization Act and the repeal of the Glass–Steagall Act and implementing cuts to the welfare state through passage of the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act.[196][198][199] The American historian Gary Gerstle writes that while Reagan was the ideological architect of the neoliberal order which was formulated in the 1970s and 1980s, it was Clinton who was its key facilitator, and as such this order achieved dominance in the 1990s and early 2000s.[200] The neoliberalism of the Clinton administration differs from that of Reagan as the Clinton administration purged neoliberalism of neoconservative positions on militarism, family values, opposition to multiculturalism and neglect of ecological issues.[201][disputed – discuss] Writing in New York, journalist Jonathan Chait disputed accusations that the Democratic Party had been hijacked by neoliberals, saying that its policies have largely stayed the same since the New Deal. Instead, Chait suggested these accusations arose from arguments that presented a false dichotomy between free-market economics and socialism, ignoring mixed economies.[202] American feminist philosopher Nancy Fraser says the modern Democratic Party has embraced a "progressive neoliberalism", which she describes as a "progressive-neoliberal alliance of financialization plus emancipation".[203] Historian Walter Scheidel says that both parties shifted to promote free-market capitalism in the 1970s, with the Democratic Party being "instrumental in implementing financial deregulation in the 1990s".[204] Historians Andrew Diamond and Thomas Sugrue argue that neoliberalism became a "'dominant rationality' precisely because it could not be confined to a single partisan identity."[205] Economic and political inequalities in schools, universities, and libraries and an undermining of democratic and civil society institutions influenced by neoliberalism has been explored by Buschman.[206]

Asia-Pacific

[edit]Scholars who emphasized the key role of the developmental state in the early period of fast industrialization in East Asia in the late 19th century now argue that South Korea, Taiwan and Singapore have transformed from developmental to close-to-neoliberal states. Their arguments are matter of scholarly debate.[207]

China

[edit]Following the death of Mao Zedong in 1976, Deng Xiaoping led the country through far ranging market-centered reforms, with the slogan of Xiǎokāng, that combined neoliberalism with centralized authoritarianism. These focused on agriculture, industry, education and science/defense.[95]

Experts debate the extent to which traditional Maoist communist doctrines have been transformed to incorporate the new neoliberal ideas. In any case, the Chinese Communist Party remains a dominant force in setting economic and business policies.[208][209] Throughout the 20th century, Hong Kong was the outstanding neoliberal exemplar inside China.[210]

Taiwan

[edit]Taiwan exemplifies the impact of neoliberal ideas. The policies were pushed by the United States but were not implemented in response to a failure of the national economy, as in numerous other countries.[211]

Japan

[edit]Neoliberal policies were at the core of the leading party in Japan, the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), after 1980. These policies had the effect of abandoning the traditional rural base and emphasizing the central importance of the Tokyo industrial-economic region.[212] Neoliberal proposals for Japan's agricultural sector called for reducing state intervention, ending the protection of high prices for rice and other farm products, and exposing farmers to the global market. The 1993 Uruguay Round of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade negotiations opened up the rice market. Neoconservative leaders called for the enlargement, diversification, intensification, and corporatization of the farms receiving government subsidies. In 2006, the ruling LDP decided to no longer protect small farmers with subsidies. Small operators saw this as favoritism towards big corporate agriculture and reacted politically by supporting the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ), helping to defeat the LDP in nationwide elections.[213]

South Korea

[edit]In South Korea, neoliberalism had the effect of strengthening the national government's control over economic policies. These policies were popular to the extent that they weakened the historically very powerful chaebol family-owned conglomerates.[214]

India

[edit]In India, Prime Minister Narendra Modi took office in 2014 with a commitment to implement neoliberal economic policies. This commitment would shape national politics and foreign affairs and put India in a race with China and Japan for economic supremacy in East Asia.[215][216]

Australia

[edit]In Australia, neoliberal economic policies (known at the time as "economic rationalism"[217] or "economic fundamentalism") have been embraced by governments of both the Labor Party and the Liberal Party since the 1980s. The Labor governments of Bob Hawke and Paul Keating from 1983 to 1996 pursued a program of economic reform focused on economic liberalisation. These governments privatised government corporations, deregulated factor markets, floated the Australian dollar and reduced trade protections.[218] Another key policy was the accords which was an agreement with unions to agree to a reduction in strikes, wage demands and a real wage cut in exchange for the implementation of social policies, such as Medicare and superannuation.[219] The Howard government continued these policies, whilst also acting to reduce union power, cut welfare and reduce government spending.[220]

Keating, building on policies he had introduced while federal treasurer, implemented a compulsory superannuation guarantee system in 1992 to increase national savings and reduce future government liability for old age pensions.[221] The financing of universities was deregulated, requiring students to contribute to university fees through a repayable loan system known as the Higher Education Contribution Scheme (HECS) and encouraging universities to increase income by admitting full-fee-paying students, including foreign students.[222] The admission of domestic full-fee-paying students to public universities was abolished in 2009 by the Rudd Labor government.[223]

Immigration to the mainland capitals by refugees have seen capital flows follow soon after, such as from war-torn Lebanon and Vietnam. Later economic migrants from mainland China also, up to recent restrictions, had invested significantly in the property markets.[224][citation needed]

New Zealand

[edit]In New Zealand, neoliberal economic policies were implemented under the Fourth Labour Government led by Prime Minister David Lange. These neoliberal policies are commonly referred to as Rogernomics, a portmanteau of "Roger" and "economics", after Lange appointed Roger Douglas minister of finance in 1984.[225]

Lange's government had inherited a severe balance of payments crisis as a result of the deficits from the previously implemented two-year freeze on wages and prices by preceding Prime Minister Robert Muldoon, who had also maintained an exchange rate many economists now believe was unsustainable.[226] The inherited economic conditions lead Lange to remark "We ended up being run very similarly to a Polish shipyard."[227] On 14 September 1984, Lange's government held an Economic Summit to discuss the underlying problems with New Zealand's economy, which lead to calls for dramatic economic reforms previously proposed by the Treasury Department.[228]

A reform program consisting of deregulation and the removal of tariffs and subsidies was put in place. This had an immediate effect on New Zealand's agricultural community, who were hit hard by the loss of subsidies to farmers.[229] A superannuation surcharge was introduced, despite having promised not to reduce superannuation, resulting in Labour losing support from the elderly. The financial markets were also deregulated, removing restrictions on interests rates, lending and foreign exchange. In March 1985, the New Zealand dollar was floated.[230] Additionally, a number of government departments were converted into state-owned enterprises, which lead to significant job losses: 3,000 within the Electricity Corporation; 4,000 within the Coal Corporation; 5,000 within the Forestry Corporation; and 8,000 within the New Zealand Post.[229]

New Zealand became a part of the global economy. The focus in the economy shifted from the productive sector to finance as a result of zero restrictions on overseas money coming into the country. Finance capital outstripped industrial capital and the manufacturing industry suffered approximately 76,000 job losses.[231]

Middle East

[edit]Beginning in the late 1960s, a number of neoliberal reforms were implemented in the Middle East.[232][233] For instance, Egypt is frequently linked to the implementation of neoliberal policies, particularly with regard to the 'open-door' policies of President Anwar Sadat throughout the 1970s,[234] and Hosni Mubarak's successive economic reforms between 1981 and 2011.[235] These measures, known as al-Infitah, were later diffused across the region. In Tunisia, neoliberal economic policies are associated with former president and de facto dictator[236] Zine El Abidine Ben Ali;[237] his reign made it clear that economic neoliberalism can coexist and even be encouraged by authoritarian states.[238] Responses to globalisation and economic reforms in the Gulf have also been approached via a neoliberal analytical framework.[239]

International organizations

[edit]The adoption of neoliberal policies in the 1980s by international institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank had a significant impact on the spread of neoliberal reform worldwide.[240] To obtain loans from these institutions, developing or crisis-wracked countries had to agree to institutional reforms, including privatization, trade liberalization, enforcement of strong private property rights, and reductions to government spending.[241][95] This process became known as structural adjustment, and the principles underpinning it the Washington Consensus.[242]

European Union

[edit]The European Union (EU), created in 1992, is sometimes considered a neoliberal organization, as it facilitates free trade and freedom of movement, erodes national protectionism and limits national subsidies.[243] Others underline that the EU is not completely neoliberal as it leaves the development of welfare policies to its constituent states.[244][245]

Traditions

[edit]Austrian School

[edit]| Part of a series on the |

| Austrian School |

|---|

|

|

|

The Austrian School is a school of economic thought originating in late-19th and early-20th century Vienna with a strong focus around the faculty of the University of Vienna. It bases its study of economic phenomena on the interpretation and analysis of the purposeful actions of individuals.[246][247][248] In the 21st century, the term has increasingly been used to denote the free-market economics of Austrian economists Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich Hayek,[249][250][251] including their criticisms of government intervention in the economy,[252] which has tied the school to neoliberal thought.[253][254][255][256]

Economists associated with the school, including Carl Menger, Eugen Böhm von Bawerk, Friedrich von Wieser, Friedrich Hayek, and Ludwig von Mises, have been responsible for many notable contributions to economic theory, including the subjective theory of value, marginalism in price theory, Friedrich von Wieser's theories on opportunity cost, Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk's theories on time preference, the formulation of the economic calculation problem, as well as a number of criticisms of Marxian economics.[257][258] Former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan, speaking of the originators of the School, said in 2000 that "the Austrian School have reached far into the future from when most of them practiced and have had a profound and, in my judgment, probably an irreversible effect on how most mainstream economists think in [the United States]".[259]

Chicago School

[edit]| Part of a series on the |

| Chicago school of economics |

|---|

The Chicago school of economics is a neoclassical school of thought within the academic community of economists, with a strong focus around the faculty of the University of Chicago. Chicago macroeconomic theory rejected Keynesianism in favor of monetarism until the mid-1970s, when it turned to new classical macroeconomics heavily based on the concept of rational expectations.[260] The school is strongly associated with University of Chicago economists such as Milton Friedman, George Stigler, Ronald Coase and Gary Becker.[261] In the 21st century, economists such as Mark Skousen refer to Friedrich Hayek as a key economist who influenced this school in the 20th century having started his career in Vienna and the Austrian school of economics.[250]

The school emphasizes non-intervention from government and generally rejects regulation in markets as inefficient, with the exception of the regulation of the money supply by central banks (in the form of monetarism). Although the school's association with neoliberalism is sometimes resisted by its proponents,[260] its emphasis on reduced government intervention in the economy and a laissez-faire ideology have brought about an affiliation between the Chicago school and neoliberal economics.[12][262]

Washington Consensus

[edit]The Washington Consensus is a set of standardized policy prescriptions often associated with neoliberalism that were developed by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank, and the US Department of Treasury for crisis-wracked developing countries.[263][264][265] These prescriptions, often attached as conditions for loans from the IMF and World Bank, focus on market liberalization, and in particular on lowering barriers to trade, controlling inflation, privatizing state-owned enterprises, and reducing government budget deficits. John Williamson, a British-born economist defined the Washington Consensus by making in 1989 10 rules that were imposed by the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and the US government on developing nations.[266] He came to strongly oppose the way those recommendations were actually imposed and their use by neoliberals.[267]

Geneva School

[edit]Historian Quinn Slobodian proposed in 2018 the existence of a so-called Geneva School of economics to describe a group of economists and political economists who gravitated in the 1920s and 1930s around the Geneva Graduate Institute, and the Geneva-based General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and League of Nations. The particular strand of political philosophy revolved around renowned economists such as Friedrich von Hayek, Wilhelm Röpke, Jacob Viner, as well as Gottfried Haberler.[268][269][270] Slobodian describes them as "ordo-globalists" who promoted the creation of global institutions to safeguard the unimpeded movement of capital across borders.[270][271] He argues the school combined the "Austrian emphasis on the limits of knowledge and the global scale with the German ordoliberal emphasis on institutions and the moment of the political decision."[269][272]

Political policy aspects

[edit]Neoliberal policies center around economic liberalization, including reductions to trade barriers and other policies meant to increase free trade, deregulation of industry, privatization of state-owned enterprises, reductions in government spending, and monetarism.[74] Neoliberal theory contends that free markets encourage economic efficiency, economic growth, and technological innovation. State intervention, even if aimed at encouraging these phenomena, is generally believed to worsen economic performance.[273]

Economic and political freedom

[edit]Economic and political freedom are inextricably linked with each other. There cannot be any question of liberty and religious and intellectual tolerance where there is no economic freedom.[274]

Many neoliberal thinkers advance the view that economic and political freedom are inextricably linked. Milton Friedman argued in his book Capitalism and Freedom that economic freedom, while itself an extremely important component of absolute freedom, is also a necessary condition for political freedom. He claimed that centralized control of economic activities is always accompanied by political repression. In his view, the voluntary character of all transactions in an unregulated market economy and the wide diversity of choices that it permits pose fundamental threats to repressive political leaders by greatly diminishing their power to coerce people economically. Through the elimination of centralized control of economic activities, economic power is separated from political power and each can serve as a counterbalance to the other. Friedman feels that competitive capitalism is especially important to minority groups since impersonal market forces protect people from discrimination in their economic activities for reasons unrelated to their productivity.[275] In The Road to Serfdom, Friedrich Hayek offered a similar argument: "Economic control is not merely control of a sector of human life which can be separated from the rest; it is the control of the means for all our ends".[121]

Free trade

[edit]A central feature of neoliberalism is the support of free trade,[276][277] and policies that enable free trade, like the North American Free Trade Agreement, are often associated with neoliberalism.[278] Neoliberals argue that free trade promotes economic growth,[279] reduces poverty,[279][276] produces gains of trade like lower prices as a result of comparative advantage,[280] maximizes consumer choice,[281] and is essential to freedom,[282][283] as they believe voluntary trade between two parties should not be prohibited by government.[284] Relatedly, neoliberals argue that protectionism is harmful to consumers,[285] who will be forced to pay higher prices for goods;[286] incentivizes individuals to misuse resources;[287] distorts investment;[287] stifles innovation;[288] and props up certain industries at the expense of consumers and other industries.[289]

Monetarism

[edit]Monetarism is an economic theory commonly associated with neoliberalism.[95] Formulated by Milton Friedman, it focuses on the macroeconomic aspects of the supply of money, paying particular attention to the effects of central banking.[290] It argues that excessive expansion of the money supply is inherently inflationary and that monetary authorities should focus primarily on maintaining price stability, even at the cost of other macroeconomic factors like economic growth.

Monetarism is often associated with the policies of the U.S. Federal Reserve under the chairmanship of economist Paul Volcker,[95] which centered around high interest rates that are widely credited with ending the high levels of inflation seen in the United States during the 1970s and early 1980s[291] as well as contributing to the 1980–1982 recession.[292] Monetarism had particular force in Chile, whose central bank raised interest rates to counter inflation that had spiraled to over 600%.[109] This helped to successfully reduce inflation to below 10%,[109] but also resulted in job losses.

Criticism

[edit]

This section may lend undue weight to certain ideas, incidents, or controversies. Please help to create a more balanced presentation. Discuss and resolve this issue before removing this message. (August 2024) |

This section possibly contains original research. (August 2024) |

Neoliberalism has faced criticism by academics, journalists, religious leaders, and activists from both the political left and right.[293][294] Notable critics of neoliberalism in theory or practice include economists Joseph Stiglitz,[295] Amartya Sen,[296] Michael Hudson,[297] Ha-Joon Chang,[298] Robert Pollin,[299] Thomas Piketty,[300][301] and Richard D. Wolff;[302] linguist Noam Chomsky;[303] geographer and anthropologist David Harvey;[95] Slovenian continental philosopher Slavoj Žižek,[304] political activist and public intellectual Cornel West;[305] Marxist feminist Gail Dines;[306] British musician and political activist Billy Bragg;[307] author, activist and filmmaker Naomi Klein;[308] head of the Catholic Church Pope Francis;[309] journalist and environmental activist George Monbiot;[310] Belgian psychologist Paul Verhaeghe;[311] journalist and activist Chris Hedges;[312] conservative philosopher Roger Scruton;[313] and the alter-globalization movement, including groups such as ATTAC. The impact of the Great Recession in 2008 has also given rise to a surge in new scholarship that criticizes neoliberalism.[314]

Market fundamentalism

[edit]The progress of the last 40 years has been mostly cultural, culminating, the last couple of years, in the broad legalization of same-sex marriage. But by many other measures, especially economic, things have gotten worse, thanks to the establishment of neo-liberal principles — anti-unionism, deregulation, market fundamentalism and intensified, unconscionable greed — that began with Richard Nixon and picked up steam under Ronald Reagan. Too many are suffering now because too few were fighting then.

Neoliberal thought has been criticized for supposedly having an undeserved "faith" in the efficiency of markets, in the superiority of markets over centralized economic planning, in the ability of markets to self-correct, and in the market's ability to deliver economic and political freedom.[316][74] Economist Paul Krugman has argued that the "laissez-faire absolutism" promoted by neoliberals "contributed to an intellectual climate in which faith in markets and disdain for government often trumps the evidence".[74] Political theorist Wendy Brown has gone even further and asserted that the overriding objective of neoliberalism is "the economization of all features of life".[317] A number of scholars have argued that, in practice, this "market fundamentalism" has led to a neglect of social goods not captured by economic indicators, an erosion of democracy, an unhealthy promotion of unbridled individualism and social Darwinism, and economic inefficiency.[318]

Some critics contend neoliberal thinking prioritizes economic indicators like GDP growth and inflation over social factors that might not be easy to quantify, like labor rights[319] and access to higher education.[320] This focus on economic efficiency can compromise other, perhaps more important, factors, or promote exploitation and social injustice.[321] For example, anthropologist Mark Fleming argues that when the performance of a transit system is assessed purely in terms of economic efficiency, social goods such as strong workers' rights are considered impediments to maximum performance.[322] He supports this assertion with a case study of the San Francisco Municipal Railway (Muni), which is one of the slowest major urban transit systems in the US and has one of the worst on-time performance rates.[323][324] This poor performance, he contends, stems from structural problems including an aging fleet and maintenance issues. He argues that the neoliberal worldview singled out transit drivers and their labor unions, blaming drivers for failing to meet impossible transit schedules and considering additional costs to drivers as lost funds that reduce system speed and performance. This produced vicious attacks on the drivers' union and brutal public smear campaigns, ultimately resulting in the passing of Proposition G, which severely undermined the powers of the Muni drivers' union.

American scholar and cultural critic Henry Giroux alleges that neoliberal market fundamentalism fosters a belief that market forces should organize every facet of society, including economic and social life, and promotes a social Darwinist ethic that elevates self-interest over social needs.[325][326][327] Marxist economic geographer David Harvey argues that neoliberalism promotes an unbridled individualism that is harmful to social solidarity.[328]

While proponents of economic liberalization have often pointed out that increasing economic freedom tends to raise expectations on political freedom,[329] some scholars see the existence of non-democratic yet market-liberal regimes and the seeming undermining of democratic control by market processes as evidence that this characterization is ahistorical.[330] Some scholars contend that neoliberal focuses may even undermine the basic elements of democracy.[330][331] Kristen Ghodsee, ethnographer at the University of Pennsylvania, asserts that the triumphalist attitudes of Western powers at the end of the Cold War and the fixation on linking all leftist political ideals with the excesses of Stalinism, permitted neoliberal, free-market capitalism to fill the void, which undermined democratic institutions and reforms, leaving a trail of economic misery, unemployment and rising economic inequality throughout the former Eastern Bloc and much of the West that fueled a resurgence of extremist nationalism.[332] Costas Panayotakis has argued that the economic inequality engendered by neoliberalism creates inequality of political power, undermining democracy and the citizen's ability to meaningfully participate.[333]